Mass-tourism seems profitable, but once we factor in the long-term costs associated with ecosystem damage, we will realise it’s not sustainable, says Ivica Trumbic, environmental consultant and expert urban planner. Through his work with the Bern Convention, Trumbic is reconciling economy and biodiversity preservation through sustainable tourism and coastal planning.

Economic development or environment preservation. For many years, these have been the seemingly mutually exclusive options that countries and regions have had to choose from. As a result, many ecosystems have been damaged in the name of the economy. But according to Ivica Trumbic, expert in urban planning and an independent environmental consultant, “economic development can go hand in hand with nature protection and conservation.”

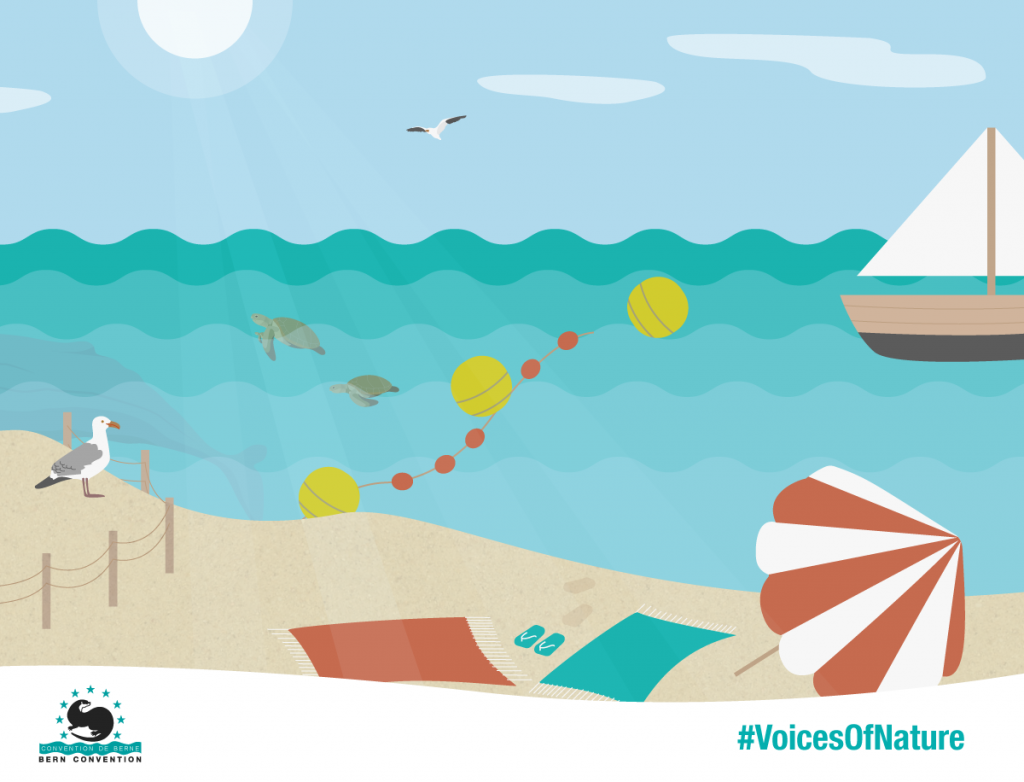

Trumbic specialises in coastal zone management and is currently working with the Bern Convention in managing protected areas for sea turtles in Turkey, Cyprus and Greece.

“In these regions, there are two important areas. First, the beaches, that are usually the nesting areas, but also the routes in the sea where the turtles pass, and they have to be taken into account as well”.

These areas are heavily affected by uncontrolled economic development because of mass tourism. Seasonal visitors have altered not only valuable habitats, such as sand dunes and coral reefs, but also the natural dynamics of coastal ecosystems. Among the causes, there is urban sprawl, huge demands for water in areas where it is scarce, uncontrolled tourist activities and marine pollution from the discharges of cruise ships or excursion boats.

According to the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), these have been the consequences of a coastal tourism management that is based only on financial criteria, while the environment is considered only in the sense of “trying to minimise the effects, given the available budget”.

“Integrated Coastal Zone Management is based on the principle that ecosystems have to be considered in their totality to manage them.”

That is why a new approach was needed. Trumbic is an expert in Integrated Coastal Zone Management (ICZM), a governance approach to unify coastal tourism and environment protection.

“Integrated Coastal Zone Management is based on the principle that ecosystems have to be taken in their totality to manage them, not only the strict narrow coastal strip that is usually taken into account. With ICZM, we manage a wider area. For example, in the sea turtle cases, marine transport routes or fishery in the surroundings will certainly affect the coastal area. That is why it is important to also take that into account in the management,” Trumbic explains.

A strategy applied at a European level

In fact, the European Union signed the Protocol to the Barcelona Convention on Integrated Coastal Zone Management in 2009 and ratified it in 2010, and now it is the approach that most European countries are implementing.

“For instance, one of the measures is to protect the coastal zone one hundred metres from the coastline, which means that there cannot be urbanisation in that area. There are some cities where this isn’t possible, and in those cases, it is necessary to have a specific urban plan,” Trumbic clarifies. With this measure, he continues, local governments protect their marine ecosystems, “but also they protect themselves from the invisible rise of the sea level and the increasing impact of sea storms that reach deeper inland.”

“It takes time to understand that the protection of ecosystems can bring economic benefits in the long term.”

Also, according to UNEP, allowing an unsustainable development of the coasts “not only impacts the environment and society but, in the long term, it affects the economic benefits of tourism, since it destroys the basis of this tourism activity.”

However, Trumbic recognises that long-term effects are usually difficult to perceive. “It takes time to understand that the protection of ecosystems can bring economic benefits in the long term. For example, if one day we start calculating our Gross Domestic product (GDP) by discounting the cost of mass tourism to ecosystems, the GDP will certainly be reduced and people will become aware.”

Similarly, there are other examples covered by the Bern Convention where a properly managed protected area, where the flora and fauna are allowed to regenerate and thrive, could become an eco-tourism attraction, so long as any touristic activities are carefully managed and do not come at the expense of the habitat and its species.

In the meantime, environmentalists such as Trumbic will continue working to reconcile biodiversity protection and the economy, proving to policy-makers that environmental protection and tourism can go hand in hand.