Islanders at loggerheads:

how one woman stepped up to protect sea turtles in Greece

March, 2021

Deadly rottweilers, kidnappers and even a life threatening assault were not enough to stop Lily Venizelos when in the 1980s she found out that the sea turtles were in danger because of touristic development in Zakynthos, Greece. Now, with the help of her own organisation and others, and the support of the Bern Convention, she is still raising her voice to save these reptiles.

Islanders at loggerheads:

how one woman stepped up to protect sea turtles in Greece

March, 2021

Deadly rottweilers, kidnappers and even a life threatening assault were not enough to stop Lily Venizelos when in the 1980s she found out that the sea turtles were in danger because of touristic development in Zakynthos, Greece. Now, with the help of her own organisation and others, and the support of the Bern Convention, she is still raising her voice to save these reptiles.

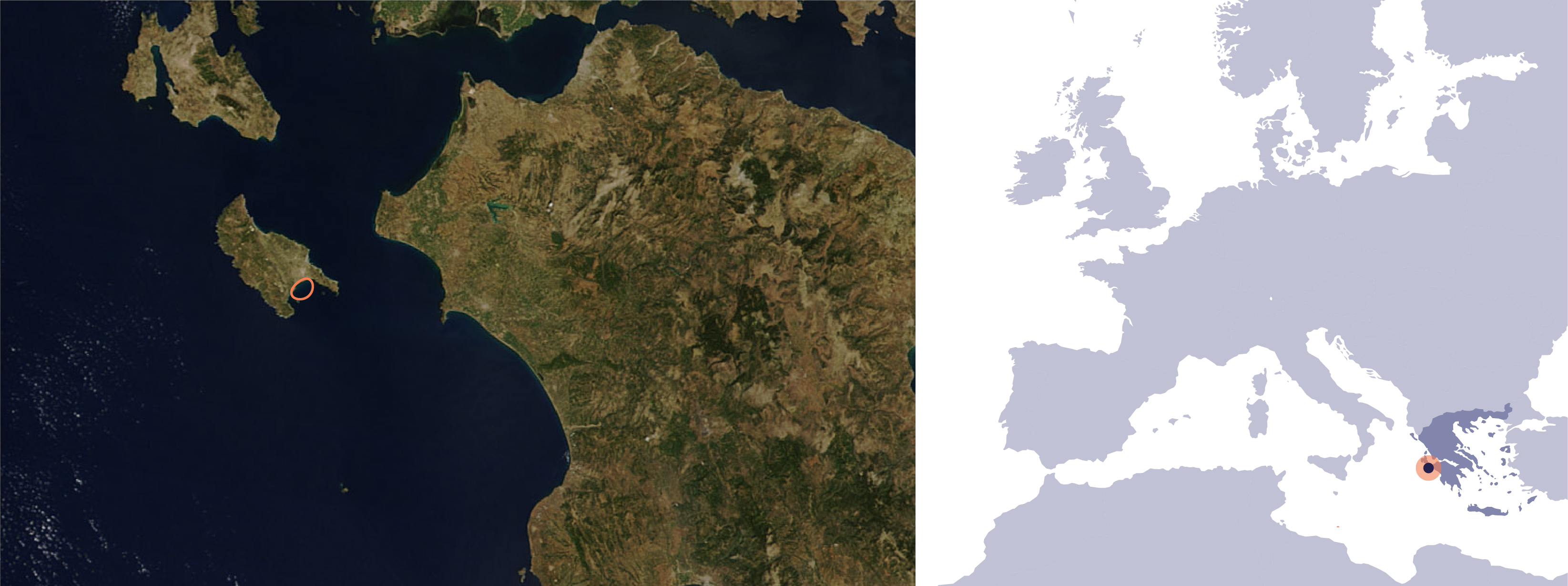

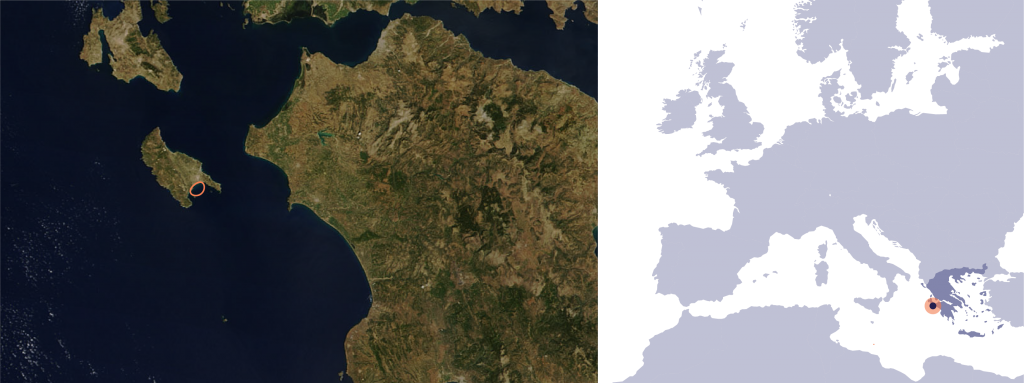

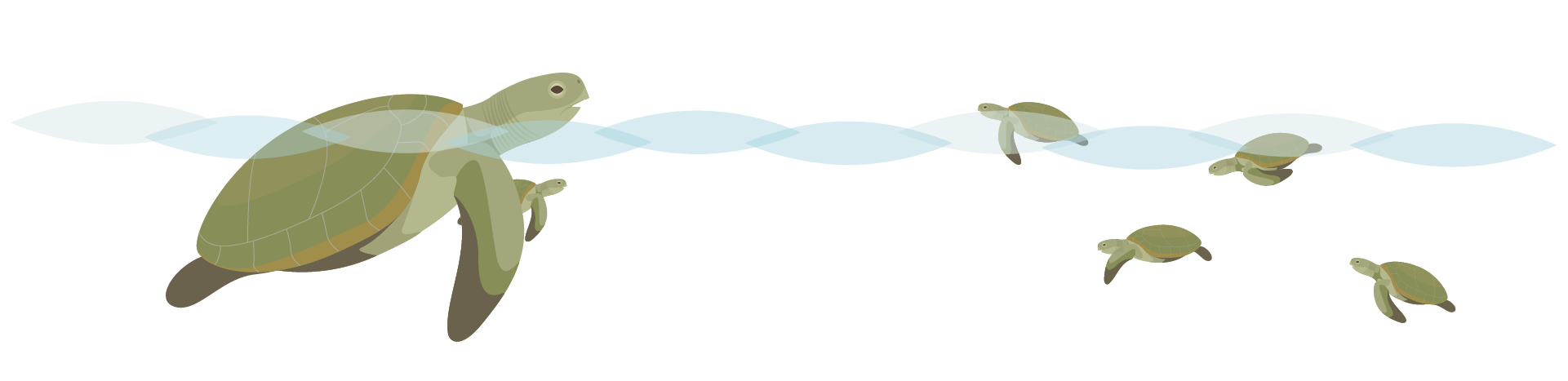

Until the 1980s, Zakynthos, a Greek island in the Ionian Sea, was a pretty quiet place, with a landscape of white sand beaches, turquoise water, where its people worked in the merchant navy and growing olive trees and grapevines. It also had a rich biodiversity and coastal areas of Laganas Bay, at the south of the island, hosted (and still do) one of the most important nesting areas for loggerhead sea turtles (Caretta caretta) in the Mediterranean.

Image by Jeff Schmaltz, MODIS Rapid Response Team, NASA/GSFC

Laganas Bay (Greece)

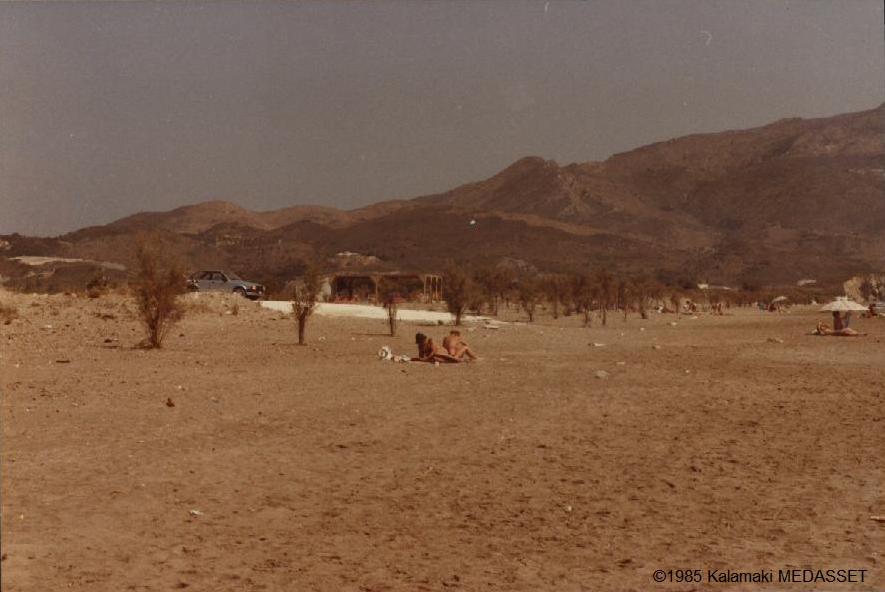

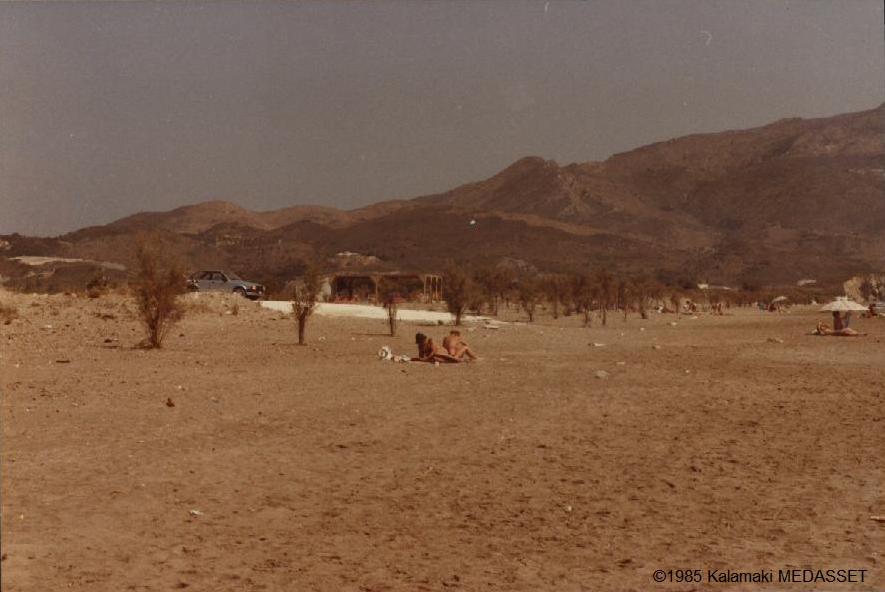

However, since the early 80s, Zakynthos has become a very popular tourist destination in Greece. Where there was silence and white sand beaches, hotels, speed boats, bright lights and loud bars arose, threatening the species’ survival.

Luckily, loggerhead turtles have not been alone in this struggle. Lily Venizelos, conservationist and founder of the Mediterranean Association to Save the Sea Turtles (MEDASSET), has been fighting for their conservation for 37 years.

She first visited Zakynthos in 1973 by pure accident. “We were on a boat and we had to anchor there because we were surprised by a hurricane,” says Venizelos. “It was absolutely like a dream. I had never imagined that there was a place like this in the world and especially in Greece,” she says.

Uncontrolled touristic development

She did not come back until seven years later. By then, the island had started to develop. “When I returned, I saw a full disaster. I was wondering if I was in the same place,” she recalls.

Photo ©1998-Gerakas-MEDASSET

Until the 1980s, Zakynthos, a Greek island in the Ionian Sea, was a pretty quiet place, with a landscape of white sand beaches, turquoise water, where its people worked in the merchant navy and growing olive trees and grapevines. It also had a rich biodiversity and coastal areas of Laganas Bay, at the south of the island, hosted (and still do) one of the most important nesting areas for loggerhead sea turtles (Caretta caretta) in the Mediterranean.

However, since the early 80s, Zakynthos has become a very popular tourist destination in Greece. Where there was silence and white sand beaches, hotels, speed boats, bright lights and loud bars arose, threatening the species’ survival.

Luckily, loggerhead turtles have not been alone in this struggle. Lily Venizelos, conservationist and founder of the Mediterranean Association to Save the Sea Turtles (MEDASSET), has been fighting for their conservation for 37 years.

She first visited Zakynthos in 1973 by pure accident. “We were on a boat and we had to anchor there because we were surprised by a hurricane,” says Venizelos. “It was absolutely like a dream. I had never imagined that there was a place like this in the world and especially in Greece,” she says.

Dams and eutrophication

According to Wulf, one of the biggest problems were the three hydropower plants situated along the Doubs and their dams along the river. “These dams make abrupt and spontaneous changes of the water table, and they cause a lot of fishes to die, especially young ones,” Wulf explains.

Apart from the three large dams, there are also small ones that do not produce much energy and have changed the original structure of the river, an issue which Pro Natura also denounces. “In this case, we even had local opposition. Some local people all of a sudden thought that it was much more beautiful like that. But they block fish movement along the river,” Wulf says.

Uncontrolled touristic development

She did not come back until seven years later. By then, the island had started to develop. “When I returned, I saw a full disaster. I was wondering if I was in the same place,” she recalls.

Indeed, the unplanned and uncontrolled coastal and touristic development was a threat to the loggerheads. The construction of roads, hotels, private houses, bars and other coastal engineering projects caused erosion and width reduction of the nesting beaches. Tourism also brought sunbeds, noise, lights and litter removal by heavy machinery that can destroy nests.

“There was disturbance of incubating nests during the day by trampling from beach users, horse-back riders and motorized vehicles,” Nikoletta Sidiropoulou says, marine biologist and the project officer from the Sea Turtle Protection Society of Greece, ARCHELON. Light pollution from human presence at night was also a problem, as hatchlings are attracted to light. They usually hatch at night or in the early morning hours and move towards the water that mirrors the moon and the stars. But the artificial lights around or near the nests disorient them and send them in the opposite direction from the sea, which can be fatal for them.

But the danger was not only in the sand. Speed boats and ‘turtle spotting’ from boats that got too close were some of the hazards that awaited the adult turtles that made it to the sea, and it was usual to find injured or even dead turtles because of these activities. There was also marine debris, like toxic plastics that are passed up the food chain and old fishing nets, where they can get entangled. Climate change has only worsened the situation, as sea level rise could potentially destroy nesting areas.

Dams and eutrophication

According to Wulf, one of the biggest problems were the three hydropower plants situated along the Doubs and their dams along the river. “These dams make abrupt and spontaneous changes of the water table, and they cause a lot of fishes to die, especially young ones,” Wulf explains.

Apart from the three large dams, there are also small ones that do not produce much energy and have changed the original structure of the river, an issue which Pro Natura also denounces. “In this case, we even had local opposition. Some local people all of a sudden thought that it was much more beautiful like that. But they block fish movement along the river,” Wulf says.

“There was disturbance of incubating nests during the day by trampling from beach users”

Indeed, the unplanned and uncontrolled coastal and touristic development was a threat to the loggerheads. The construction of roads, hotels, private houses, bars and other coastal engineering projects caused erosion and width reduction of the nesting beaches. Tourism also brought sunbeds, noise, lights and litter removal by heavy machinery that can destroy nests.

“There was disturbance of incubating nests during the day by trampling from beach users”

“There was disturbance of incubating nests during the day by trampling from beach users, horse-back riders and motorized vehicles,” Nikoletta Sidiropoulou says, marine biologist and the project officer from the Sea Turtle Protection Society of Greece, ARCHELON. Light pollution from human presence at night was also a problem, as hatchlings are attracted to light. They usually hatch at night or in the early morning hours and move towards the water that mirrors the moon and the stars. But the artificial lights around or near the nests disorient them and send them in the opposite direction from the sea, which can be fatal for them.

But the danger was not only in the sand. Speed boats and ‘turtle spotting’ from boats that got too close were some of the hazards that awaited the adult turtles that made it to the sea, and it was usual to find injured or even dead turtles because of these activities. There was also marine debris, like toxic plastics that are passed up the food chain and old fishing nets, where they can get entangled. Climate change has only worsened the situation, as sea level rise could potentially destroy nesting areas.

The threats for the sea turtles

Tourism

Plastic & derelict fishing gear

Global warming

Boats

Light pollution

Coastal development

The threats for the sea turtles

Tourism

Plastic & derelict fishing gear

Global warming

Boats

Light pollution

Coastal development

Conservation or economic interests

Aware of all of the threats, Lily Venizelos started her movement by looking for support among local people. But most of the population from Zakynthos were not very excited about the turtles. “They were afraid that with the conservation movement, we would stop the development on the island. I was very much aware of that,” Venizelos says.

However, she did not give up, and finally found some local groups that were interested in the environmental wellbeing of the beaches and the sea turtles. Eventually, word of this lady who wanted to stop unsustainable development and was starting to gain followers reached the ears of big investors and they tried to stop her.

Dams and eutrophication

According to Wulf, one of the biggest problems were the three hydropower plants situated along the Doubs and their dams along the river. “These dams make abrupt and spontaneous changes of the water table, and they cause a lot of fishes to die, especially young ones,” Wulf explains.

Apart from the three large dams, there are also small ones that do not produce much energy and have changed the original structure of the river, an issue which Pro Natura also denounces. “In this case, we even had local opposition. Some local people all of a sudden thought that it was much more beautiful like that. But they block fish movement along the river,” Wulf says.

“Locals were afraid that with the conservation movement, we would stop the development on the island”

“My life was threatened many times,” says the conservationist. She was chased by one landowner’s rottweilers, held against her will, and nearly strangled. But in 1985 she appealed to the Bern Convention to bring international attention to the situation at Zakynthos. After the Standing Committee conducted an on-the-spot appraisal and discussed the case, in 1987 it adopted Recommendation No. 9 (1987) , urging the Greek government to take measures.

The Standing Committee recognised that the loggerhead turtle was “seriously endangered mainly as a result of habitat loss in its nesting grounds, which suffer important deterioration as a result of touristic activities” and acknowledged the importance of the Laganas Bay beaches for the survival of the species.

In order to protect the area, they requested that the new hotels had to be built at least two hundred meters from the sea and illegal buildings had to be removed. Any walls and concrete built in the optimal sites for turtle nesting had to be removed, too.

The Committee also recommended banning speedboats, along with setting speed limits and appropriate corridors for the rest of the boats, and penalising the use of deck chairs and sunshades near the nesting areas.

Regarding the lights, it requested replacing them or at least reorienting them to minimise their impact on the turtles. Also, it recommended setting legal limits to the number of people allowed on the beaches.

To protect the area even more, the Committee suggested that Laganas Bay be declared a natural park. They also recommended better collaboration between the Greek authorities and the non-profit organisation now known as ARCHELON to keep carrying out the monitoring, research and public awareness they had been performing. Their monitoring has been running now for 37 years.

After that, Laganas Bay became the first Marine National Park of Greece under a Presidential Decree in 1999. However, according to Venizelos, although “laws now exist”, they have not been enforced because of a lack of resources.

“The National Marine Park doesn’t have enough money. The Park is supposed to have guards that can watch if anything illegal is getting done, but there is no money to pay them,” she says.

Sidiropoulou, who is currently leading ARCHELON’s monitoring and public awareness project in Zakynthos, says that the scale and the speed of touristic development on the island since 1999 was “far bigger than what was anticipated”.

“Sea turtles in Laganas bay are used as a touristic attraction: most of the nesting beaches are very crowded and an ever increasing number of turtle spotting boats are always after sea turtles swimming in the waters of the bay”, she declares.

She is also concerned about law violations: “There are maritime regulations in place which describe no-go areas, speed limits, ban of anchoring and fishing activity, but violations of the legislation are recorded every season.”

According to ARCHELON, only in the nesting season of 2017 there were recorded 68,047 violations regarding removal of beach furniture, and 486 boats breached the speed limit. Consequently, sea turtles in Laganas Bay continue to have serious threats, even with the drop in tourism due to the COVID-19 outbreak.

Dams and eutrophication

According to Wulf, one of the biggest problems were the three hydropower plants situated along the Doubs and their dams along the river. “These dams make abrupt and spontaneous changes of the water table, and they cause a lot of fishes to die, especially young ones,” Wulf explains.

Apart from the three large dams, there are also small ones that do not produce much energy and have changed the original structure of the river, an issue which Pro Natura also denounces. “In this case, we even had local opposition. Some local people all of a sudden thought that it was much more beautiful like that. But they block fish movement along the river,” Wulf says.

COVID-19 and its (non) effect in sea turtle nesting

A very high number of nests was recorded by ARCHELON, in collaboration with the National Marine Park in 2020, the third highest recorded since 1983. Although it may seem that recent lockdowns and the low number of tourist arrivals would be the cause, research shows that is not the case.

“Our investigation has shown that loggerheads start their migration route towards their nesting sites as early as January and February, every 2-3 years, so the numbers of females coming to nest on Zakynthos could not have been affected by the lockdown in Europe,” Sidiropoulou declares.

According to ARCHELON, in the nesting season of 2017 alone, 68,047 violations were recorded regarding removal of beach furniture, and 486 boats breached the speed limit. Consequently, sea turtles in Laganas Bay continue to have serious threats, even with the drop in tourism due to the COVID-19 outbreak.

Recognition from

NGOs, including MEDASSET and ARCHELON, have continued to raise their voice for better implementation of conservation measures in Laganas Bay. Now, they have achieved the reopening of the Bern Convention case for Laganas Bay after 30 years. The Standing Committee said that they “acknowledge with concern the information of the complainant organisations” and urged the national authorities “to enforce existing legislation, to raise awareness and inform local stakeholders especially illegal business owners on the importance of preserving the habitat and to impose penalties when the law is not upheld.”

“We think that this reopening of the case file is an opportunity to finally get them to do what they need to do,” Venizelos believes.

The conservationist says that she is optimistic about the case. 47 years after she had to anchor in Zakynthos, she is still raising her voice to protect the loggerhead sea turtles and the landscape of the island. But now she is not just a woman against big investors. “I’m getting older, but we have some excellent people in MEDASSET who will continue to take care of the sea turtles.”

Dams and eutrophication

According to Wulf, one of the biggest problems were the three hydropower plants situated along the Doubs and their dams along the river. “These dams make abrupt and spontaneous changes of the water table, and they cause a lot of fishes to die, especially young ones,” Wulf explains.

Apart from the three large dams, there are also small ones that do not produce much energy and have changed the original structure of the river, an issue which Pro Natura also denounces. “In this case, we even had local opposition. Some local people all of a sudden thought that it was much more beautiful like that. But they block fish movement along the river,” Wulf says.

Conservation or economic interests

Aware of all of the threats, Lily Venizelos started her movement by looking for support among local people. But most of the population from Zakynthos were not very excited about the turtles. “They were afraid that with the conservation movement, we would stop the development on the island. I was very much aware of that,” Venizelos says.

However, she did not give up, and finally found some local groups that were interested in the environmental wellbeing of the beaches and the sea turtles. Eventually, word of this lady who wanted to stop unsustainable development and was starting to gain followers reached the ears of big investors and they tried to stop her.

“Locals were afraid that with the conservation movement, we would stop the development on the island”

“My life was threatened many times,” says the conservationist. She was chased by one landowner’s rottweilers, held against her will, and nearly strangled. But in 1985 she appealed to the Bern Convention to bring international attention to the situation at Zakynthos. After the Standing Committee conducted an on-the-spot appraisal and discussed the case, in 1987 it adopted Recommendation No. 9 (1987) , urging the Greek government to take measures.

The Standing Committee recognised that the loggerhead turtle was “seriously endangered mainly as a result of habitat loss in its nesting grounds, which suffer important deterioration as a result of touristic activities” and acknowledged the importance of the Laganas Bay beaches for the survival of the species.

In order to protect the area, they requested that the new hotels had to be built at least two hundred meters from the sea and illegal buildings had to be removed. Any walls and concrete built in the optimal sites for turtle nesting had to be removed, too.

The Committee also recommended banning speedboats, along with setting speed limits and appropriate corridors for the rest of the boats, and penalising the use of deck chairs and sunshades near the nesting areas.

Regarding the lights, it requested replacing them or at least reorienting them to minimise their impact on the turtles. Also, it recommended setting legal limits to the number of people allowed on the beaches.

To protect the area even more, the Committee suggested that Laganas Bay be declared a natural park. They also recommended better collaboration between the Greek authorities and the non-profit organisation now known as ARCHELON to keep carrying out the monitoring, research and public awareness they had been performing. Their monitoring has been running now for 37 years.

After that, Laganas Bay became the first Marine National Park of Greece under a Presidential Decree in 1999. However, according to Venizelos, although “laws now exist”, they have not been enforced because of a lack of resources.

“The National Marine Park doesn’t have enough money. The Park is supposed to have guards that can watch if anything illegal is getting done, but there is no money to pay them,” she says.

Sidiropoulou, who is currently leading ARCHELON’s monitoring and public awareness project in Zakynthos, says that the scale and the speed of touristic development on the island since 1999 was “far bigger than what was anticipated”.

“Sea turtles in Laganas bay are used as a touristic attraction: most of the nesting beaches are very crowded and an ever increasing number of turtle spotting boats are always after sea turtles swimming in the waters of the bay”, she declares.

She is also concerned about law violations: “There are maritime regulations in place which describe no-go areas, speed limits, ban of anchoring and fishing activity, but violations of the legislation are recorded every season.”

According to ARCHELON, in the nesting season of 2017 alone, 68,047 violations were recorded regarding removal of beach furniture, and 486 boats breached the speed limit. Consequently, sea turtles in Laganas Bay continue to have serious threats, even with the drop in tourism due to the COVID-19 outbreak.

COVID-19 and its (non) effect in sea turtle nesting

A very high number of nests was recorded by ARCHELON, in collaboration with the National Marine Park in 2020, the third highest recorded since 1983. Although it may seem that recent lockdowns and the low number of tourist arrivals would be the cause, research shows that is not the case.

“Our investigation has shown that loggerheads start their migration route towards their nesting sites as early as January and February, every 2-3 years, so the numbers of females coming to nest on Zakynthos could not have been affected by the lockdown in Europe,” Sidiropoulou declares.

According to ARCHELON, the analysis of these time series has shown that the annual nesting activity on Zakynthos is greatly fluctuating, as is the case for most sea turtle populations around the world. However, the annual nest numbers do not show any long-term trend.

NGOs, including MEDASSET and ARCHELON, have continued to raise their voice for better implementation of conservation measures in Laganas Bay. Now, they have achieved the reopening of the Bern Convention case for Laganas Bay after 30 years. The Standing Committee said that they “acknowledge with concern the information of the complainant organisations” and urged the national authorities “to enforce existing legislation, to raise awareness and inform local stakeholders especially illegal business owners on the importance of preserving the habitat and to impose penalties when the law is not upheld.”

“We think that this reopening of the case file is an opportunity to finally get them to do what they need to do,” Venizelos believes.

The conservationist says that she is optimistic about the case. 47 years after she had to anchor in Zakynthos, she is still raising her voice to protect the loggerhead sea turtles and the landscape of the island. But now she is not just a woman against big investors. “I’m getting older, but we have some excellent people in MEDASSET who will continue to take care of the sea turtles.”

Recognition from

Timeline

1977

Dimitris Margaritoulis, the future founder of ARCHELON, discovers that loggerheads nest in Laganas Bay and publish his observations of the period 1977-1979 in the scientific journal Biological Conservation.

1980

Touristic development starts.

1981 – 1982

First nest monitoring project funded by WWF-International through the Hellenic Society for the Protection of Nature.

1983

ARCHELON, the Sea Turtle Protection Society of Greece, is founded and organises systematic nest monitoring, tagging and in situ public awareness projects.

1985

Venizelos calls the attention of the Standing Committee of the Bern Convention to the situation at Zakynthos.

1987

The Standing Committee of the Bern Convention adopts Recommendation No. 9 (1987) on the protection of Caretta caretta in Laganas bay.

1988

MEDASSET is founded.

1999

Laganas Bay becomes the first Marine National Park of Greece under a Presidential Decree.

2020

Follow-up conservation assessment reports are submitted by MEDASSET and ARCHELON. The Standing Committee of the Bern Convention decides to reopen the file.

Timeline

1977

Dimitris Margaritoulis, the future founder of ARCHELON, discovers that loggerheads nest in Laganas Bay and publish his observations of the period 1977-1979 in the scientific journal Biological Conservation.

1980

Touristic development starts.

1981 – 1982

First nest monitoring project funded by WWF-International through the Hellenic Society for the Protection of Nature.

1983

ARCHELON, the Sea Turtle Protection Society of Greece, is founded and organises systematic nest monitoring, tagging and in situ public awareness projects.

1985

Venizelos calls the attention of the Standing Committee of the Bern Convention to the situation at Zakynthos.

1987

The Standing Committee of the Bern Convention adopts Recommendation No. 9 (1987) on the protection of Caretta caretta in Laganas bay.

1988

MEDASSET is founded.

1999

Laganas Bay becomes the first Marine National Park of Greece under a Presidential Decree.

2020

Follow-up conservation assessment reports are submitted by MEDASSET and ARCHELON. The Standing Committee of the Bern Convention decides to reopen the file.