Saving

the sturgeons:

a joint effort to revive the most endangered group of species on the planet

March, 2021

Decades of overexploitation and human disturbance have driven sturgeon populations to the verge of collapse all around the world. Looking to desperately change the course of things, a coalition of conservationists and researchers sprung into action to design an action plan for reversing the mass extinction of sturgeons in Europe. The Bern Convention has played a central role in turning the plan into reality and bringing countries within and outside the EU together to push for the conservation of this ancient species.

Saving the sturgeons:

a joint effort to revive the most endangered group of species on the planet

March, 2021

Decades of overexploitation and human disturbance have driven sturgeon populations to the verge of collapse all around the world. Looking to desperately change the course of things, a coalition of conservationists and researchers sprung into action to design an action plan for reversing the mass extinction of sturgeons in Europe. The Bern Convention has played a central role in turning the plan into reality and bringing countries within and outside the EU together to push for the conservation of this ancient species.

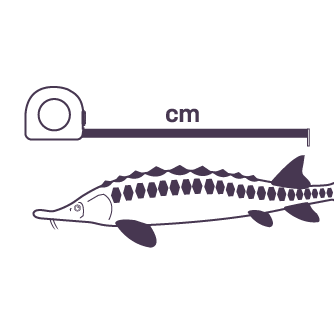

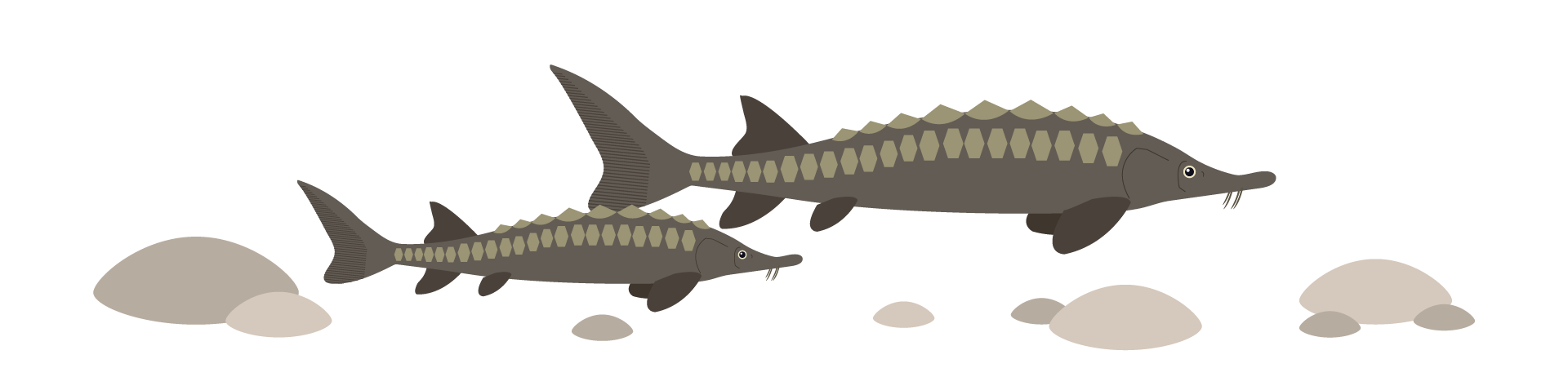

Over 200 million years ago, when dinosaurs still roamed the Earth, a group of fish species appeared which still exists today. These living fossils, as they are often called by researchers, have remained nearly unchanged in their appearance until the present day.

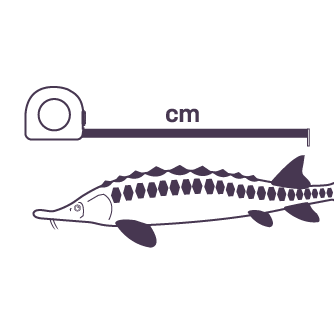

In their size, sturgeons certainly seem to belong to another time: they can reach up to eight meters in length and 1,5 tons in weight.

Sturgeons outlived the dinosaurs, but a new species would emerge a couple of hundred million years later that would really put their existence at risk: us.

Sturgeons are a group of 27 fish species that live solely in the Northern Hemisphere, on the American and Eurasian continents, the latter of which is home to the majority of sturgeon species at risk of extinction.

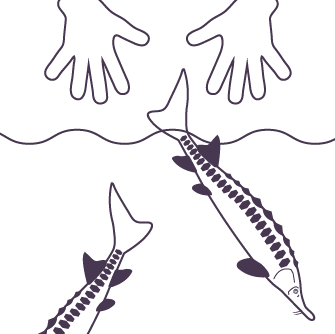

Sturgeon are extremely long lived fish, some of which can reach a lifespan of over 100 years. All sturgeon are migratory species, and with a few freshwater exceptions, most of them spend a considerable amount of their lives in the sea and migrate to rivers for spawning. Sturgeon spawn several times during their long life cycles, which sets them apart from fish like salmon that spawn only once.

The migratory nature of the sturgeon poses a challenge for their protection, as conservation measures cannot be pinned under the legislation of one country or geographical region alone. That is why, when the WWF and the scientific association World Sturgeon Conservation Society (WSCS) started to work on an action plan for saving this group of species in Europe, they quickly realised they needed the support of an organisation whose impact would span over both EU and non-EU countries alike. It was the Bern Convention that both NGOs identified as the best possible umbrella for the action plan.

Sturgeon’s range

Dams and eutrophication

According to Wulf, one of the biggest problems were the three hydropower plants situated along the Doubs and their dams along the river. “These dams make abrupt and spontaneous changes of the water table, and they cause a lot of fishes to die, especially young ones,” Wulf explains.

Apart from the three large dams, there are also small ones that do not produce much energy and have changed the original structure of the river, an issue which Pro Natura also denounces. “In this case, we even had local opposition. Some local people all of a sudden thought that it was much more beautiful like that. But they block fish movement along the river,” Wulf says.

Last cry for help

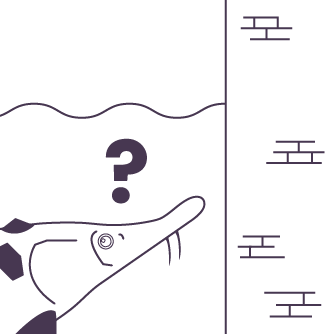

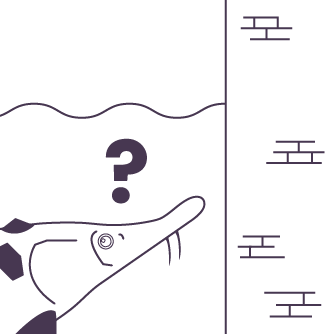

Sturgeons mature late during their lifespan and do not reproduce annually. This makes them particularly vulnerable to population declines, since any losses in their population take multiple years to recover. To make matters worse, the fish are often prevented from reproducing altogether, as their direct harvesting mainly takes place on their migration routes.

The situation is especially bad in Europe, where naturally-reproducing sturgeon populations are left only in the Lower Danube river and North-Western Black Sea. The most dramatic sturgeon population declines have been witnessed only during the last three decades, when deep drops in catches began to be documented.

Human activity is largely to blame for this evolution. One of the biggest threats to the species is overexploitation. Sturgeon roe, better known as caviar, is an extremely sought after luxury product. In many areas, hunt for this delicacy has been the main reason for the diminishing of sturgeon stocks.

In addition to overfishing, sturgeons’ migration routes between water systems in many parts of the world have been blocked or altered by dams and hydropower plants.

These developments, together with the habitat altering effects of climate change, have forced the sturgeon under a title no species should have to bear. In the video clip below WWF’s Sturgeon Initiative Leader Beate Striebel-Greiter tells more about the alarming state of the fish.

A final indicator of the extreme urgency for taking action, a desperate cry for help came in 2010, when the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) declared the sturgeon the most threatened group of species in the world. Unfortunately, even ten years after the statement, no significant improvement in the European sturgeon stocks has been detected.

Although individual national and regional initiatives to save the species had emerged in different parts of Europe during the course of the years, it had become evident that more coordinated and larger scale cooperation between countries was needed.

It was WWF, more specifically its Central and Eastern European branch, and the WSCS that began to advance the creation of a Europe-wide action plan for reversing the gloomy-looking fate of the sturgeon.

In the video below, Jörn Geßner, who is Vice-president of the World Sturgeon Conservation Society, explains the importance of preserving sturgeons in their natural habitats.

Dams and eutrophication

According to Wulf, one of the biggest problems were the three hydropower plants situated along the Doubs and their dams along the river. “These dams make abrupt and spontaneous changes of the water table, and they cause a lot of fishes to die, especially young ones,” Wulf explains.

Apart from the three large dams, there are also small ones that do not produce much energy and have changed the original structure of the river, an issue which Pro Natura also denounces. “In this case, we even had local opposition. Some local people all of a sudden thought that it was much more beautiful like that. But they block fish movement along the river,” Wulf says.

“If we lose these species, they are gone forever. This is not something that happens during our grandchildren’s lifetime, we could actually witness that extinction ourselves”

Bern Convention as the common denominator

The original idea was to implement the action plan on the EU level to align it with other EU directives like the Habitat Directive and the Water Framework Directive. However, as sturgeon populations are shared by both EU as well as non-EU countries alike, especially in the Black Sea region, it quickly became clear that EU legislation alone wasn’t going to be enough.

Inspired by initiatives created for migratory bird species, the founding organisations of the initiative decided to approach the Standing Committee to the Bern Convention with hopes that it could bring all the countries and regions involved together. In a similar vein to sturgeons, migratory birds breed in certain countries and nest in others, and thus are important for more than one ecosystem.

The resulting plan, called the Pan-European Action Plan for Sturgeons (PANEUAP), entails a set of objectives, conditions for accomplishing them as well as actions to be taken in order to prevent the irreversible extinction of European sturgeons.

Dams and eutrophication

According to Wulf, one of the biggest problems were the three hydropower plants situated along the Doubs and their dams along the river. “These dams make abrupt and spontaneous changes of the water table, and they cause a lot of fishes to die, especially young ones,” Wulf explains.

Apart from the three large dams, there are also small ones that do not produce much energy and have changed the original structure of the river, an issue which Pro Natura also denounces. “In this case, we even had local opposition. Some local people all of a sudden thought that it was much more beautiful like that. But they block fish movement along the river,” Wulf says.

Objectives for the Pan-European Action Plan for sturgeons

Remaining wild populations are protected from accidental and directed removal of individuals

Population structure is actively supported to reverse the decline

Sturgeon habitats are protected and restored in key rivers

Sturgeon migration is secured or facilitated

Timely and continuous detection of population sizes and changes in remaining wild stocks

Eliminate illegal trade of all sturgeon products

The Action Plan was adopted by the Standing Committee to the Bern Convention in November 2018, and also endorsed for implementation under the EU Habitats Directive in May 2019. The time frame of the Action Plan extends for ten years until 2029.

An inherently democratic process

An analysis at the beginning of the development of the PANEUAP shed light onto what had prevented the success of previous national and regional action plans. Shortcomings included a lack of priority setting and of clear responsibilities between different authorities.

“There’s an overlap of authorities that need to work together. We have fishing, water administration and conservation authorities, who can all sit in three different ministries depending on a country’s organisation – and even within fishing there might be differences between sea and river responsibilities. Ownership of coordination was not spelled out clearly in many action plans. They weren’t developed together with the different authorities,” WWF’s Beate Striebel explains.

The development of the PANEUAP has been an open process from the very beginning, bringing together the voices of various different actors from public authorities to NGOs and scientific institutions. These stakeholders have had appointed opportunities to comment and provide insight for the plan along the way.

Important is also the way the Action Plan has come about in the first place.

“Even the simple fact that we as civil society can bring such a proposal to the Bern Convention, for the states to discuss and decide on, shows that this is a thoroughly democratic process,” Striebel says.

At the national and regional levels, it’s also essential to involve all the river users for the implementation of the Action Plan to succeed, says WCSC’s Jörn Geßner. “In Germany we did a roundtable involving fisheries, inland navigation, local stakeholders, anglers, and so on, to make sure that they understood what we were planning to do, and to gather their support for the necessary activities. The same story goes for France and the Netherlands, for instance.”

The implementation of the Action Plan is still taking its first steps. By 2021, the European Union and the Council of Europe are expected to establish a Group of Experts, including Bern Convention representatives of national environment ministries as well as international and national civil society organisations and experts acting for the conservation of sturgeons. This team will set up and oversee coordinated mechanisms to implement the plan across Europe, while increasing the awareness, capacity and ownership of relevant stakeholders.

A pitstop for evaluating the overall effectiveness of the Action Plan has been planned for 2024, five years after the beginning of the implementation. However, countries involved are encouraged to take the PANEUAP as a blueprint for their respective plans and name institutions responsible for coordinating actions in a certain time frame on the national level.

Important progress has already been made on the national level. In the Netherlands and Ukraine, new national sturgeon action plans have recently been approved, in France an existing plan is under revision, and in Romania discussions regarding a national plan have started.

While there is reason to be hopeful, noticeable changes will take time to manifest, says Geßner: “The smaller sturgeon species mature at an age of six to eight years, the largest species take 15 to 20 years for first maturation. It’s almost like forestry: you put the seedlings in, and then you have to wait for almost a generation in order to see whether that’s effective or not.”

Dams and eutrophication

According to Wulf, one of the biggest problems were the three hydropower plants situated along the Doubs and their dams along the river. “These dams make abrupt and spontaneous changes of the water table, and they cause a lot of fishes to die, especially young ones,” Wulf explains.

Apart from the three large dams, there are also small ones that do not produce much energy and have changed the original structure of the river, an issue which Pro Natura also denounces. “In this case, we even had local opposition. Some local people all of a sudden thought that it was much more beautiful like that. But they block fish movement along the river,” Wulf says.

“The fact that we as civil society can bring such a proposal to the Bern Convention, for the states to discuss and decide on, shows that this is a thoroughly democratic process”

Changing attitudes as a source for change

Raising public awareness plays an important role in the PANEUAP, in fact, it has been listed as one of the enabling actions to reach the primary objectives of the plan. According to Beate Striebel from WWF it is too often overlooked in the preparation of conservation measures.

“We always fall for our own traps, because we think we are communicating the risks nonstop. We think that everyone should know what’s happening by now and neglect that there are so many topics out there, that people have other things on their mind,” she says.

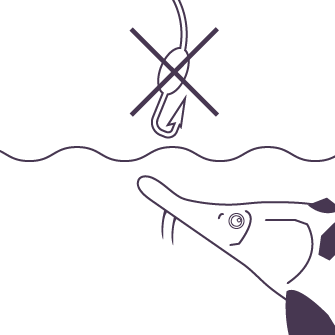

Awareness raising is important for many reasons, one of them being the need to stop the illegal trade of the sturgeon, both for its meat and caviar. Even with regulations in place, the origins of sturgeon products are often falsely declared or labelled.

In addition, many people do not necessarily understand the importance of sturgeons for ecosystems or what might happen to the water systems without this fish. It is difficult to perceive the severity of losing a species as the consequences will be visible only after nothing can be done anymore.

“If we lose these species, they are gone forever. This is not something that will happen during our grandchildren’s lifetime, we could actually witness that extinction ourselves,” says Beate Striebel.

The implementation of the Action Plan is still at the beginning, but it is without a doubt a necessary leap towards reviving the sturgeon. It has all the potential to create actual change, but it is competing against something that is hard to beat.

Time.

Dams and eutrophication

According to Wulf, one of the biggest problems were the three hydropower plants situated along the Doubs and their dams along the river. “These dams make abrupt and spontaneous changes of the water table, and they cause a lot of fishes to die, especially young ones,” Wulf explains.

Apart from the three large dams, there are also small ones that do not produce much energy and have changed the original structure of the river, an issue which Pro Natura also denounces. “In this case, we even had local opposition. Some local people all of a sudden thought that it was much more beautiful like that. But they block fish movement along the river,” Wulf says.

“We fall for our own traps, because we think we are communicating the risks nonstop. We think that everyone should know what’s happening by now and neglect that people have other things on their mind”

The development of the Pan-European Action Plan for the Conservation of Sturgeon

2017

- First draft submitted for review (input from experts from e.g. UNEP, IUCN, Bonn Convention & European Commission)

- Second draft shared with Bern Convention national focal points

2018

- Input from the participants of the High Level Conference for the Protection of Sturgeon

- Final version submitted to the Standing Committee to the Bern Convention

- Adoption of Action Plan by the Bern Convention Standing Committee

2019

- Endorsement for implementation under the EU Habitats Directive

2019-2029

- Implementation of the Action Plan

ver 200 million years ago, when dinosaurs still roamed the Earth, a group of fish species appeared which still exists today. These living fossils, as they are often called by researchers, have remained nearly unchanged in their appearance until the present day.

In their size, sturgeons certainly seem to belong to another time: they can reach up to eight meters in length and 1,5 tons in weight.

Sturgeons outlived the dinosaurs, but a new species would emerge a couple of hundred million years later that would really put their existence at risk: us.

Sturgeon’s range

Sturgeons are a group of 27 fish species that live solely in the Northern Hemisphere, on the American and Eurasian continents, the latter of which is home to the majority of sturgeon species at risk of extinction.

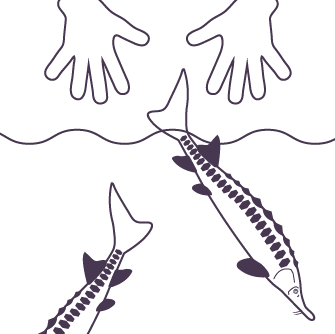

Sturgeon are extremely long lived fish, some of which can reach a lifespan of over 100 years. All sturgeon are migratory species, and with a few freshwater exceptions, most of them spend a considerable amount of their lives in the sea and migrate to rivers for spawning. Sturgeon spawn several times during their long life cycles, which sets them apart from fish like salmon that spawn only once.

The migratory nature of the sturgeon poses a challenge for their protection, as conservation measures cannot be pinned under the legislation of one country or geographical region alone. That is why, when the WWF and the scientific association World Sturgeon Conservation Society (WSCS) started to work on an action plan for saving this group of species in Europe, they quickly realised they needed the support of an organisation whose impact would span over both EU and non-EU countries alike. It was the Bern Convention that both NGOs identified as the best possible umbrella for the action plan.

Last cry for help

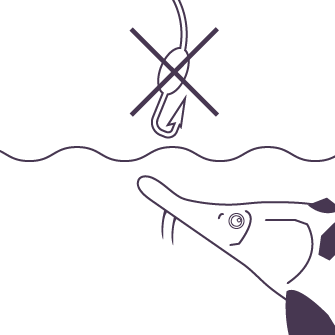

Sturgeons mature late during their lifespan and do not reproduce annually. This makes them particularly vulnerable to population declines, since any losses in their population take multiple years to recover. To make matters worse, the fish are often prevented from reproducing altogether, as their direct harvesting mainly takes place on their migration routes.

The situation is especially bad in Europe, where naturally-reproducing sturgeon populations are left only in the Lower Danube river and North-Western Black Sea. The most dramatic sturgeon population declines have been witnessed only during the last three decades, when deep drops in catches began to be documented.

Human activity is largely to blame for this evolution. One of the biggest threats to the species is overexploitation. Sturgeon roe, better known as caviar, is an extremely sought after luxury product. In many areas, hunt for this delicacy has been the main reason for the diminishing of sturgeon stocks.

“If we lose these species, they are gone forever. This is not something that happens during our grandchildren’s lifetime, we could actually witness that extinction ourselves”

In addition to overfishing, sturgeons’ migration routes between water systems in many parts of the world have been blocked or altered by dams and hydropower plants.

These developments, together with the habitat altering effects of climate change, have forced the sturgeon under a title no species should have to bear. In the video clip below WWF’s Sturgeon Initiative Leader Beate Striebel-Greiter tells more about the alarming state of the fish.

A final indicator of the extreme urgency for taking action, a desperate cry for help came in 2010, when the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) declared the sturgeon the most threatened group of species in the world. Unfortunately, even ten years after the statement, no significant improvement in the European sturgeon stocks has been detected.

Although individual national and regional initiatives to save the species had emerged in different parts of Europe during the course of the years, it had become evident that more coordinated and larger scale cooperation between countries was needed.

It was WWF, more specifically its Central and Eastern European branch, and the WSCS that began to advance the creation of a Europe-wide action plan for reversing the gloomy-looking fate of the sturgeon.

In the video below, Jörn Geßner, who is Vice-president of the World Sturgeon Conservation Society, explains the importance of preserving sturgeons in their natural habitats.

Bern Convention as the common denominator

The original idea was to implement the action plan on the EU level to align it with other EU directives like the Habitat Directive and the Water Framework Directive. However, as sturgeon populations are shared by both EU as well as non-EU countries alike, especially in the Black Sea region, it quickly became clear that EU legislation alone wasn’t going to be enough.

Inspired by initiatives created for migratory bird species, the founding organisations of the initiative decided to approach the Standing Committee to the Bern Convention with hopes that it could bring all the countries and regions involved together. In a similar vein to sturgeons, migratory birds breed in certain countries and nest in others, and thus are important for more than one ecosystem.

The resulting plan, called the Pan-European Action Plan for Sturgeons (PANEUAP), entails a set of objectives, conditions for accomplishing them as well as actions to be taken in order to prevent the irreversible extinction of European sturgeons.

Read more about PANEUAP

Objectives for the Pan-European Action Plan for sturgeons

Remaining wild populations are protected from accidental and directed removal of individuals

Population structure is actively supported to reverse the decline

Sturgeon habitats are protected and restored in key rivers

Sturgeon migration is secured or facilitated

Timely and continuous detection of population sizes and changes in remaining wild stocks

Eliminate illegal trade of all sturgeon products

The Action Plan was adopted by the Standing Committee to the Bern Convention in November 2018, and also endorsed for implementation under the EU Habitats Directive in May 2019. The time frame of the Action Plan extends for ten years until 2029.

An inherently democratic process

An analysis at the beginning of the development of the PANEUAP shed light onto what had prevented the success of previous national and regional action plans. Shortcomings included a lack of priority setting and of clear responsibilities between different authorities.

“There’s an overlap of authorities that need to work together. We have fishing, water administration and conservation authorities, who can all sit in three different ministries depending on a country’s organisation – and even within fishing there might be differences between sea and river responsibilities. Ownership of coordination was not spelled out clearly in many action plans. They weren’t developed together with the different authorities,” WWF’s Beate Striebel explains.

“The fact that we as civil society can bring such a proposal to the Bern Convention, for the states to discuss and decide on, shows that this is a thoroughly democratic process”

The development of the PANEUAP has been an open process from the very beginning, bringing together the voices of various different actors from public authorities to NGOs and scientific institutions. These stakeholders have had appointed opportunities to comment and provide insight for the plan along the way.

Important is also the way the Action Plan has come about in the first place.

“Even the simple fact that we as civil society can bring such a proposal to the Bern Convention, for the states to discuss and decide on, shows that this is a thoroughly democratic process,” Striebel says.

At the national and regional levels, it’s also essential to involve all the river users for the implementation of the Action Plan to succeed, says WCSC’s Jörn Geßner. “In Germany we did a roundtable involving fisheries, inland navigation, local stakeholders, anglers, and so on, to make sure that they understood what we were planning to do, and to gather their support for the necessary activities. The same story goes for France and the Netherlands, for instance.”

The implementation of the Action Plan is still taking its first steps. By 2021, the European Union and the Council of Europe are expected to establish a Group of Experts, including Bern Convention representatives of national environment ministries as well as international and national civil society organisations and experts acting for the conservation of sturgeons. This team will set up and oversee coordinated mechanisms to implement the plan across Europe, while increasing the awareness, capacity and ownership of relevant stakeholders.

A pitstop for evaluating the overall effectiveness of the Action Plan has been planned for 2024, five years after the beginning of the implementation. However, countries involved are encouraged to take the PANEUAP as a blueprint for their respective plans and name institutions responsible for coordinating actions in a certain time frame on the national level.

Important progress has already been made on the national level. In the Netherlands and Ukraine, new national sturgeon action plans have recently been approved, in France an existing plan is under revision, and in Romania discussions regarding a national plan have started.

While there is reason to be hopeful, noticeable changes will take time to manifest, says Geßner: “The smaller sturgeon species mature at an age of six to eight years, the largest species take 15 to 20 years for first maturation. It’s almost like forestry: you put the seedlings in, and then you have to wait for almost a generation in order to see whether that’s effective or not.”

Changing attitudes as a source for change

Raising public awareness plays an important role in the PANEUAP, in fact, it has been listed as one of the enabling actions to reach the primary objectives of the plan. According to Beate Striebel from WWF it is too often overlooked in the preparation of conservation measures.

“We always fall for our own traps, because we think we are communicating the risks nonstop. We think that everyone should know what’s happening by now and neglect that there are so many topics out there, that people have other things on their mind,” she says.

Awareness raising is important for many reasons, one of them being the need to stop the illegal trade of the sturgeon, both for its meat and caviar. Even with regulations in place, the origins of sturgeon products are often falsely declared or labelled.

“We fall for our own traps, because we think we are communicating the risks nonstop. We think that everyone should know what’s happening by now and neglect that people have other things on their mind”

In addition, many people do not necessarily understand the importance of sturgeons for ecosystems or what might happen to the water systems without this fish. It is difficult to perceive the severity of losing a species as the consequences will be visible only after nothing can be done anymore.

“If we lose these species, they are gone forever. This is not something that will happen during our grandchildren’s lifetime, we could actually witness that extinction ourselves,” says Beate Striebel.

The implementation of the Action Plan is still at the beginning, but it is without a doubt a necessary leap towards reviving the sturgeon. It has all the potential to create actual change, but it is competing against something that is hard to beat.

Time.